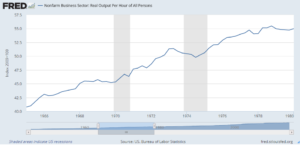

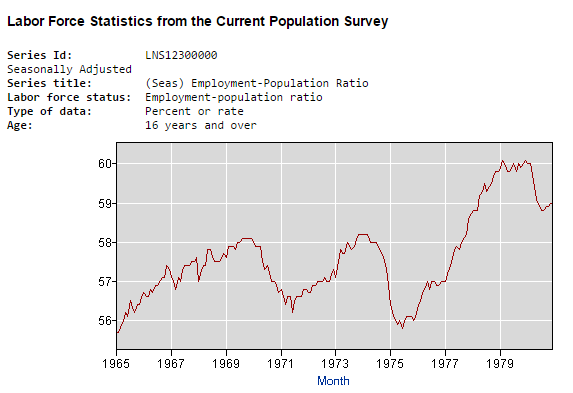

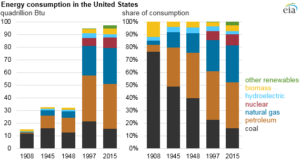

- The coal industry in the US has been on a downward trajectory since about 1970s.

- Despite what is reported this is not primarily because of environmental regulations.

- It’s also not because people are embracing alternative energy.

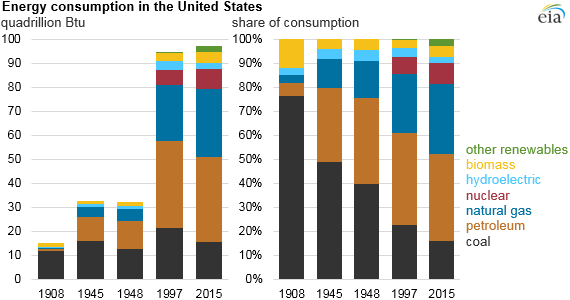

The reality is completely different and it’s well summarized by this graph anyone can go find on the energy information agency’s website.

What about India? Well, while that is a possible market, it turns out India has a lot of it’s own coal it can mine. And guess what… Indian miners earn a lot less than US miners. So unless the future of US coal is somehow extracting the coal for less than they can do it in India (including shipping costs and potential import taxes) there’s no future there either.

CAVEAT

I will say this. It’s POSSIBLE that some kind of new use for coal is discovered that previously doesn’t exist and can’t be predicted. It’s also possible that we run out of natural gas or petroleum before those sources are replaced and the reliance on coal comes back.

That sounds far fetched, but consider two examples from history.

Standard Oil’s primary product was kerosene for lighting households. That market was crushed by electricity as it became available which forced them to pivot to gasoline. Before the automobile gasoline was a dangerous byproduct that was considered worthless.

Similarly, during the early days of whaling, it was only the whale oil that was extracted, the bone was thrown away. It wasn’t until bone was used for making things similar to the way plastic is used today that it became valuable.

So there are examples from history where things that look like they are dying find a second life because of new uses. But those things don’t require intervention… the market tends to discover them.

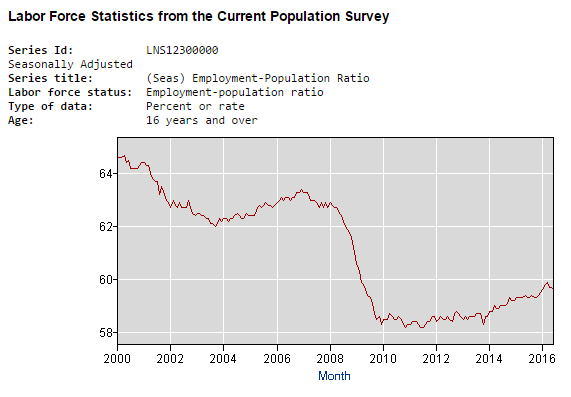

WHAT ABOUT THOSE MINERS?

This is the really nasty issue. I’ve commented a lot about basic income and I still think this is a potentially good idea, but it’s also long term and doesn’t help people today.

There are longer term ideas, like investing in high energy wind farms in Western Kentucky. Those also required skill workers for both construction and maintenance and Western Kentucky has a combination of moderate the high winds as well as lots of land. It’s also a lot healthier to work on a wind turbine than in a coal mine, and the clean up costs are not quite as high. The problem, of course, is that wind isn’t all that efficient today so the economics don’t make sense…. but hey… the economics for coal don’t make sense either so if we’re going to subsidize maybe it should be in something future looking?

Another possibility is to focus on natural gas production in Kentucky. The major problem with this is that other sources are much cheaper to develop and extract.

The state itself also should look for future investments in high tech industry generally. Somewhat more outlandish thing like Pittsburg’s focus on self driving cars. The city essentially restructuring itself from steel to technology.

Right now Kentucky gets 85% of it’s energy from coal vs. the national average of 32%. I suspect this is because the industry has a lot of power and is desperately trying to cling to the past at the cost of the current and future people of the state.

I’m not picking on Kentucky. It’s a beautiful state with vast resources and some of the most breathtaking scenery in the country. It’s not fair that hard working people who spent decades of their lives doing back breaking work in dangerous conditions get the shaft because of long term economic trends beyond their control. It’s just as bad that they are being lied to and given false hope so that a small number of people can extract the last pound of flesh for their own enrichment.

I believe the way our of these situation is a combination of building for the future while exercising some compassion and care for people when they become victims of circumstances beyond their control. I actually think it’s entirely valid to declare a state of emergency in cases like this and treat the people in these areas the way we would people caught in hurricanes or massive fires. While those are “naturally occurring” disasters, they are just as devastating and just as difficult to control at the individual level.