THE STORY OF PAUL AND PAULAThere are two young people at the beginning of their careers: Paul and Paula.

Both finished school with no debt, live within their means and have identical spending and saving habits. Both have annual income of $100,000 (I know, it’s high, but it’s easy to do math on 100 vs 55 so bear with me).

Paul and Paula are quantum entangled and as such over the next 40 years they both experienced exactly the same things: they married at the same time, had children at the same time, endured identical medical problems, and had duplicated investment returns. In short everything was exactly the same, except one thing…

Paula derives her income from work, whereas Paul derives his income from a trust fund.

We’re ignoring, for a moment, the implications of this difference… more time, less stress, access to health insurance, 401ks, and on and on. We’re going to pretend that all of that is equal although I would contend that the inherited income has far more financial benefits than the earned income.

WHAT HAPPENS – THE MICROCOSM

It’s April 10th.

Paul and Paula are both procrastinators and so they are scrambling to do their taxes.

Both have fairly simple taxes at this stage in their lives. They are single, have no children, and do not own a home. They also live in a state with no income taxes and so their procrastination will not be a major source of trouble.

Paula has a W2 from her employer but no other sources of income. Paul has his investment income but no other source of income.

Let’s see how their taxes compare.

With no other deductions, sources of income or write offs, Paula will pay $18,553 of taxes… roughly 18.5%.

Paul on the other hand will pay roughly, $7,979 on his $100,000 of qualified dividends.

Now, I KNOW that of course it’s never this simple; but bear with me.

In terms of monthly cash flow, Paula has $6,787.25 whereas Paul has $7,668.

HOW DOES THIS IMPACT SAVINGS?

Continuing the story, let’s look at two scenarios.

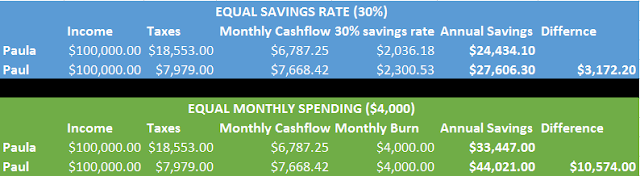

In Scenario 1, both save 30% of their post tax income and adjust their cost of living appropriately.

In Scenario 2, both have the same cost of living, $4000/mo, and save what’s left over.

Here’s how that looks:

This demonstrates two things.

1) How big of a difference in savings it makes if you save a large % of your income and then adjust your cost of living.

2) A lower tax based due to source of income has a dramatic impact on savings rate if lifestyle is equal.

In other words, if your source of income is from an inheritance, you can have a much higher savings rate while maintaining the same quality of life as someone who has to earn their income via a W2 based job.

HOW THIS GROWS OVER TIME

I’m sure everyone understands the basic concept of compound interest, but it’s always fun to visualize.

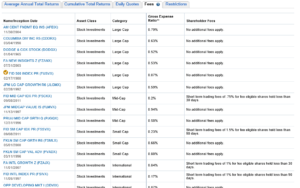

So let’s say both Paul and Paula are going to work for 40 years, invest their money in a boring 70/30 stock/bond index fund (insert pitch for vanguard here) and they had a reasonably modest 4% inflation adjusted return over that time period. After that 40 years they both plan to retire.

How did that turn out for them?

Here’s a chart showing annual savings as well as accumulated net worth based on the fixed $4,000 monthly spend scenario:

PAULA’S DATA

PAUL’S DATA

Paula’s accumulated savings are $3.17 million whereas Paul’s are $4.18 million, just under 25% more.

POST RETIREMENT LIFE

So now they’ve retired. Paula has a very respectable $3.17 million saved and Paul has a somewhat larger $4.18 million saved.

Both of these are incredibly good scenarios and well beyond what most people end up with after 40 years of work which shows how important the forces of consistent savings and avoiding bad luck are.

That said, let’s assume both Paul and Paula

believe in the 4% rule and start withdrawing 4% of their savings over the next 25 years. They also will continue to get a return on their savings of 5% per year.

Since they are connected through some bizzaro human quantum entanglement they will die on precisely the same day 25 years after they both retire from work.

At the end of those 25 years, Paula’s assets are $3.88 million and Paul’s are $5.06 million… quite a bit more.

Additionally, Paul spent a total of $4.61 million (164k/year on average) while Paula spent “just” $3.5 million (140k/year on average).

That means that when they die, in addition to having significantly more to spend during his retirement and not needing to have income from a job, Paul ALSO gets to leave considerably more to his heirs.

BUT WAIT THERE’S MORE

Consider… we didn’t even include Paul’s initial trust of a few million to provide him with the 100k income over those 40 years of work.

Let’s further assume that Paul gets the $2.5 million from his trust fund the day he retires, and we add it to his day 1 retirement pool of.$4.1 million.

How do things look during and after Paul’s retirement?

In a word, not bad. Paul now has $8.09 million at the end of 25 years of retirement while also being able to spend $7.35 million (an average of 294K/ year).

That means in addition to spending more than double what Paula spends in retirement, he will also have two and a half times more money to leave his heirs.

Not a bad deal for being born lucky.

CONCLUSION

If you inherit enough money that it pays you investment income that is similar to a full time job, you get MASSIVE benefits… like my dad said it’s like playing monopoly with twice the starting money and 4 dice instead of 2.

Now I’m not saying that investment income should be taxed like regular income, because I understand that within a single lifetime that amounts to double taxation and would be a pretty brutal (and I think unfair) hit on retirees. That said, I do believe that inherited wealth is somewhat different. Specifically I think the “luck” factor in inheritance is significantly higher than the “luck” factor in saving diligently, having a successful business, etc.

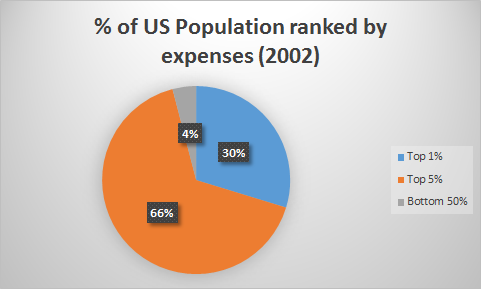

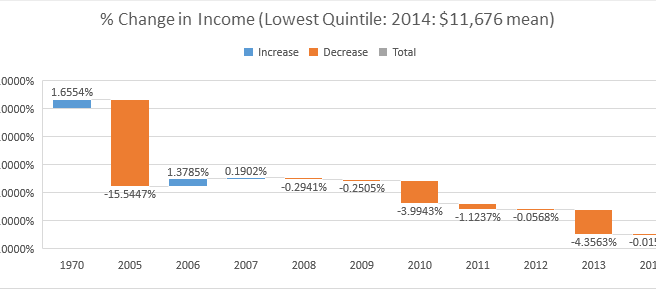

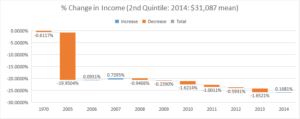

Additionally, if you multiply this effect over generations it’s obvious that it acts to concentrate massive amounts of wealth in the hands of a few people. Those people will not be able to spend the money efficiently in order to ensure the economy keeps moving, technology improves, innovation is spurred etc. Instead they are likely to hoard and stagnate the flow of capital. That is VERY bad for capitalism and society.

I don’t have a single, simple solution, but I do think that society needs a fairly comprehensive way of preventing those things from happening. One way, of course, is to have an incredibly “progressive” estate tax, which is what Bernie Sanders is suggesting. Assuming that it isn’t “game-able” by extremely wealthy people… and that’s a big assumption… that would either redistribute their wealth more evenly or encourage them to use it/give it away before they die.

I personally LOVE “The giving pledge” and think it should be extended to include people other than billionaires.

It does bring up the challenge of trying to decide who/how the money should be distributed, but I think almost any system is better than the ovarian lottery.